Passover

We would sit down fifteen, sometimes twenty, to the table on seder nights: my parents; the maiden aunts -- Birdie, Len, and before the war, Dora, sometimes Annie; cousins of varying degree, visiting from France or Switzerland; and always a stranger or two who would come. There was a beautiful, embroidered tablecloth that Annie had brought us from Jerusalem, gleaming white and gold on the table. My mother, knowing that sooner or later there would be accidents, always had a preemptive "spill" herself -- she would manage, somehow, to tip a bottle of red wine onto the tablecloth, and thereafter no guest would be embarrassed if they knocked over a glass. Though I knew she did this deliberately, I could never predict how or when the "accident" would occur; it always looked absolutely spontaneous and authentic. (She would immediately spread salt on the wine stain, and it became much paler, almost disappearing; I wondered why salt had this power.)

-- Oliver Sacks, Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood (New York: Knopf, 2001), 174-75.

Yoke Your Paranoia to Your Technical Knowledge

Common wisdom holds that 140,000 generally churchgoing Americans in Iraq are locked in mortal combat with some of the world’s most serious monotheists. To me, a new, less orthodox faith seems to have arisen, something far more personal and circumstantial. You could see it every time you watched a grunt throw away a box of Charms candies that came in the field rations (bad luck) or toss rounds that had been dropped (no matter how much you cleaned them, bullets that had been dropped always jammed). Like so many others, I had been inclined to believe in the bromide "There are no atheists in foxholes," but based upon my admittedly less-than-systematic observations, there were at least as many blessed lance corporals, lucky ladybugs, stuffed giraffes, coins, and saved M16 rounds as there were rosary beads. The marines I lived with seemed to have moved on from the Twenty-third Psalm and were now deep into One Hundred Years of Solitude.

One afternoon I was watching tv at an Iraqi house that some Marine advisors had commandeered. It was a lazy afternoon, not much going on in-sector. We were all sitting around watching The Breakfast Club on a wide-screen. On the floor in front of us a lieutenant was cleaning a .50-caliber machine gun with what looked like Victorian surgical instruments. As Molly Ringwald declaimed her particular strain of late-eighties suburban anomie, the lieutenant's hands flashed over the weapon in practiced, weirdly maternal gestures. A microwave oven buzzed in the background. The echoes of domesticity were unignorable: We were like a deranged, unexplainably well-armed family. An artillery forward observer who was new to the team said, "Man, we haven't gotten IED'd in awhile." The team's executive officer, a

high-strung captain who'd been a logistics officer back in the States stomped into the living room and yelled, "God damn it, dude, I know you didn't just say that." He craned over melodramatically to some plywood shelves near the corporal's head and knocked on one of them. Guys were always doing this sort of thing. Anytime somebody started talking about how much time they had left or the fact that recently they'd had a run of good luck, eyes began to search frantically for a horizontal surface to knock on.A couple of weeks later I read in the New York Times that one of the team's Humvees had struck an enormous IED, killing two marines. After I returned to the States, I received an e-mail from the team leader saying that the Times report had been in error, but this welcome correction failed to fully erase the causal chain that had haunted my mind in the interregnum. A corporal had given voice to an idle observation about not having been IED'd in a while and some of his comrades had been killed. And, even now, this is the memory trace, the psychological residue that remains: in Iraq thinking the wrong thoughts can kill you.

The trick was to focus your mind, to yoke your paranoia to your technical knowledge. One master sergeant I met in Al Qa'im told me that sometimes he could sense muj attacks before they came. I was skeptical until the day I saw him do it. We were in a convoy of six Humvees doing a standard security patrol when he picked up a radio handset and said, "We're gonna get hit today, I can feel it." When a small plume of dust arched in the sky ahead of us -- the shock wave from the IED hitting us a few seconds later -- he just shook his head. He didn't consider himself a metaphysician or anything; the skill was just something he'd developed over time in the field, the ability to interpolate between thousands of seemingly arbitrary micro-events and anticipate the narrative, to see the dance in the data. Scientists who study this sort of phenomenon refer to it as apophenia -- a handy piece of nomenclature to be sure, but to my haunted mind, the master sergeant was nothing less than a wizard, and I tried to stay as close to him as I could.

-- David J. Morris, "The Big Suck: Notes from the Jarhead Underground," Virginia Quarterly Review, Winter 2007.

Anatomy Lesson

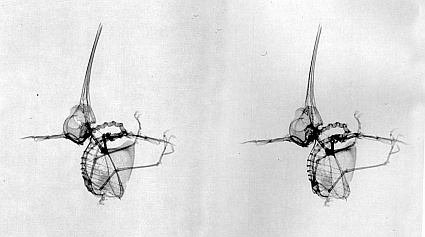

Once, when my nephew Jonathan was a few months old, I picked up a packed of X-rays marked "J. Sacks" that had been left in the lounge. I started to leaf through them curiously, then perplexedly, then with horror -- for Jonathan was a nice-looking little baby, and no one would have guessed, without the X-rays, that he was hideously deformed. His pelvis, his little legs -- they scarcely looked human.

I went to my mother with the X-rays, shaking my head. "Poor Jonathan . . . " I started.

My mother looked puzzled. "Jonathan?" she said. "Jonathan is fine."

"But the X-rays," I said, "I've been looking at his X-rays."

My mother looked blank, then burst into a roar of laughter, and laughed until tears ran down her face. "J" did not stand for Jonathan, she finally said, but for another member of the household, Jezebel. Jezebel, our new boxer, had had some blood in her urine, and my mother had taken her to hospital to have a kidney X-ray. What I had taken for grotesquely deformed human anatomy was, in fact, perfectly normal canine anatomy. How could I have made such an absurd mistake? The least knowledge, the least common sense, would have made it all clear to me -- my mother, a professor of anatomy, shook her head in disbelief.

-- Oliver Sacks, Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood (New York: Knopf, 2001), 240.

A Shark Inside a Wave

William Willis's raft voyage from Peru to Samoa in 1954:

In the patterns of light around the raft, he once thought he saw an octopus extending enormous tentacles toward him, and he ran for his ax. Lying one afternoon asleep on the deck, he suddenly woke and in a wave looming above him saw a shark that looked ready to attack him. He jumped up to defend himself. The shark fell, and the raft rose on the wave that had contained it. Occasionally at night, the sparks of phosphorescence thrown up by the bow would seem to merge with the sky, and he would feel as if he were sailing among the stars.

Even though he wore sunglasses, the sun eventually blinded him, and he had to remain for hours at a time in the cabin, bathing his eyes with salt water for the pain. The first island where he might have landed was surrounded by reefs and had no shore. No one answered his radio call for help, so he had to sail past it. During a squall he heard a crash in the cabin but was too busy to address it. The cat had toppled the parrot's cage and killed the parrot. Willis sewed its remains in a piece of sail, put them in the cage, and lowered them overboard. After finding finding no way to enter a harbor on a second island, he saw an American ship headed toward him, and they towed him to land. He had been at sea for 112 days.

-- Alec Wilkinson, The Happiest Man in the World: An Account of the Life of Papa Neutrino (New York: Random House, 2007), 68.

A Small Whale Inside a Wave

I enjoyed the Atlantic crossing an indecent amount. Even when the wind wasn't blowing I liked being there -- I didn't want any noise so I just drifted about until the wind came back. I read books, wrote little computer programs, enjoyed the sea. I didn't want it to be over. I wanted to move slowly across the water and never get anywhere.

One windy day I saw a small whale inside a wave. The waves were steep that day and I saw a grayish object in the blue -- it was a whale swimming along, inside the top of the wave, looking me over. The whale would ride to the top of each new wave and eye my boat, as if in a passing railroad car of water.